In Western philosophy, the imagination only appears a few times, and generally is quickly dismissed, or swept aside because it complicates our focus on reasoning, knowing, getting to the objective truth of things.

According to Cornelius Castoriadis,[1] Aristotle tried to discuss the imagination, but lost sight of it. Then tripped over it somewhere else but didn’t know what it was. It reappears in Kant’s famous Critique of Pure Reason, but is removed from the revised edition, because it confused his critics. Hegel tried to tease it out, but floundered and misplaced it. Heidegger rediscovered Kant’s imagination, and then hid it away again. And Freud put it front and center when he outlined the central role of the unconscious, and the importance of dreams, but never used the word.

Johann Arnason suggests that what is most important on Castoriadis’s repositioning of the imagination is that he has ruptured a long standing equation of being with determination.[2] This is much too complex to explore here. In simple terms, it underlies the basic causal explanations sought in most western philosophical and scientific explanation: the idea that if something exists, it must have been caused (determined) by something else. I’ll came back to this, too, a few times in the discussion that follows. For the moment let’s just observe that this idea of causality has obstructed a clear view of the full scope of human creativity.

In Eastern philosophy, where all of perceived reality is an illusion (maya), the imagination has always had a more central role – but no more positive. Cutting through the illusions of maya is necessary to get to the absolute truth.

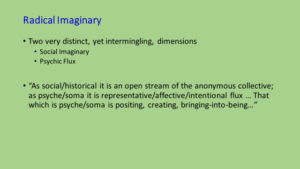

One of the greatest challenges in elucidating the centrality of the imagination to human life is first distinguishing and then reintegrating two different fields: the social imaginary, and the radical imaginary of the psyche. Problems arise already when we begin to make this distinction, for the radical imaginary is not of the psyche, it is the psychic flux – the representative/affective/intentional flux that posits/creates/brings-into-being.

We discussed this at some length in the Psyche and Subjectivity (which you can read here). I’ll elaborate on that in a moment, but first let me briefly clarify some aspects of the social field.

The first thing you might have noted in the slide above is that rather than referring to the social, Castoriadis refer to society as the social/historical. In developing his understanding of human creativity he argues that history is not something that happens to an entity called society, but rather history is the very unfolding of society itself. In this view, a society is the acquired sedimentation of its history, or rather (in more Castoriadian terms) the accumulated institution of its imaginary significations.

In short, he argues that it is misleading to speak of history and society has two separate things, when a society is nothing other than its history. We’ll look more closely at social imaginary significations, and thus the social imaginary field, after an elaboration of the psychic flux – the radical imagination of the singular person.

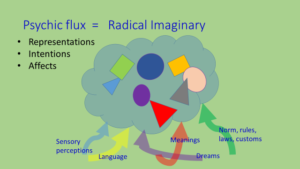

One of Castoriadis’s significant contributions is to understand the entirety of psychical life as imaginary. That is, in contrast to previous thinking about such things, he does not see the imagination as a separate faculty of the mind; certainly not as a secondary or problematic faculty. Instead, the psyche and the imagination are synonymous – the process of converting sensory perceptions, for example, into representations, intentions and affects is an imagining – a process of the radical imaginary. In short, the imagination is the primary process of the psyche; perceiving and reasoning are faculties of the imagination.

[Note: I previously described this imagery here]

Kant, for example, made a sharp distinction between the perceptive, the rational and the imaginative (or perception, understanding and imagination).

Castoriadis reconceives the imagination as the ground upon which perception happens, and upon which reasoning can begin to add two and two together. In other words, the imagination is psychic activity per se.

He doesn’t use comparisons like this one – but of course, at the most basic level every animal is involved in some degree of perceiving and reasoning – with the fight or flight response being a simple logical mechanism, a binary logical reasoning: either this or that. A reasoning based on assessment of a perceived threat. In this case, all animals have a psychic flux and an imagination of sorts. But in most cases this reasoning and imagining capacity is limited to the functional imperative of survival and reproduction – what Freud called the survival instinct.

Another notable breakthrough is to offer a corrective to the reductionist understanding of the survival instinct as a biological imperative. Something like this functionalist reduction is found in every effort to explain human behaviour through genetic explanations, or evolutionary imperatives. Every biologist, psychologist and economist who seeks the evolutionary benefits that explain any particular human behaviour have fallen into this trap. And it’s a very compelling trap for a number of reasons – one of the more obvious being that it corresponds to a basic axiom about causality: the idea that everything happens for a reason From this perspective, it follows that the scientists’ job is to uncover that reason.

But while that might take us a long way in understanding the behaviours of other animal species, Castoriadis argues that the human psyche has defunctionalized. Our relatively bigger brain has surplus capacity which serves no necessary function – which leaves it free to make things up.

It is in that psychic surplus that we find room for human creativity – our capacity to make something out of nothing. This is one of the more controversial ideas in his work – for it is a basic axiom of physics, as well as theology, that you cannot get something from nothing (unless you are God). In response to critics of this idea, Castoriadis explained that he’s not claiming that these things appear out of thin air. In this explanation he distinguishes between creation “from nothing” “in nothing” and “with nothing”. Some continue to argue that this is too fine a distinction – but they cannot offer an explanation of why people have created horror movies, jazz music or macramé pot hangers, none of which appear to have any real evolutionary or survival value. We also have to make some pretty long stretches to explain the romance novel, and the action adventure movie – not to mention the church and the wide variety of religious rituals and festivals.

Castoriadis is primarily interested in the creation of various forms of society and social institutions, rather than the fine arts and crafts. He argues that in basic causal terms, the same survival inputs would produce the same survival outputs – which raises a question of why marriage customs, gender roles and religious practices differ so significantly from one culture to the next. His answer here is a creative capacity and impulse that greatly exceeds any survival imperatives.

An important effect of the defunctionalisation of the psyche, he says, is that representational pleasure has supplanted organ pleasure. Of course we still enjoy eating, copulating and other pleasures of the flesh. But speaking, singing, reading, writing and creating works of art have become “higher” forms of pleasure. These are the measures by which we evaluate cultural differences, but they’re also the dimensions through which we identify ourselves. Yes, some of us are foodies – but it is the ways that our culinary skills and knowledge exceed survival requirements that stand out here. And some people’s identities emphasize their sexual preferences – need I say this is primarily an issue for those for whom their sexual practices deviate from the breeding norms?

Still, those are all relatively mundane examples compared with what Castoriadis was primarily concerned – the form of the institution of society itself. For him, the Ancient Greek creation of a democratic form of government was a radical breakthrough, bringing into being a form of collective self-governance that was entirely unprecedented. He treats this as the epitome of creatio ex nihilo (creation from nothing).

Backing down a little, he also sees many of our words, meaning, ideas and institutions as having no basis in reality or necessity. One of his favourite examples is God, which he maintains is created from nothing to serve some social purposes, but not survival functions.

I’ll try to remember to come back to that. But note that in the discussion I’ve moved from individual creations like identity and sexuality to collective creations like forms of government and… significations like god or the divine which, like words more generally, are meaningless and empty if they are not shared. That is, these things belong to the field of the social imaginary.

I recently posted a gripe on FB about the changing meaning of the word literally – a pedantic gripe about which much has been written. I said:

So, we’ve accepted that it’s in the normal course of English for words to assume different meanings over time.

We are reminded of this regularly recently because the word “literally” seems to have come to mean anything but literally. Yes, it was annoying, but then we remembered that it’s a living language, and things change, and there’s no profit in expending energy over young people changing the meaning of words. That’s what they do. That’s what we did.

And it’s really not a problem. Sometimes. When someone says “OMG, I literally died when he showed up!” you know they didn’t, literally, die. Annoying, but not confusing.

So, tonight, I’m expecting guests at 6. At 6.20 I send a text asking how far away they are. I get a reply: “I was literally just looking for your number to let you know we’ll be 3, maybe 3-1/2 hours late.”

Back in the days when literally only meant literally, I would have taken this literally. But today I have to wonder if what she really means is that she had some vague feeling that maybe there was something that she should be doing while waiting to catch a plane three hours later than planned, and when she got my text it occurred to her what it was. Of course, if she had simply left out the word literally, I would have none of this dialogue going on, and would have accepted that she was in the process of contacting me when I contacted her.

So, yeah, meanings of words change, and there’s little to be done about it. But during the transition periods, a lot of clarity is lost.

My point in sharing this here is to illustrate the dialogical character of meaning. Whenever a word is used, it is used to convey meaning between two (or more) people – and contrary to all of the Humpty Dumpty’s of the world, no one ever has total control over what a word or sentence means .

Anyway, to a more considered analysis of social imaginary significations, let me briefly revisit the trope of clouds and boxes (which was previously discussed here).

Most of what we do in language can be seen as attempting to force clouds into boxes.

We’re almost always dealing with clouds – changing, fluid and dynamic shape-shifters.

We’re almost always trying to force them into boxes – neat and clearly delineated, fixed and unchanging, clear cut and easy to judge.

The problem occurs in all uses of language, and in all social imaginary significations. Language is just one dimension – although perhaps the most obvious dimension – of what Castoriadis calls social imaginary significations (SIS). Referring to words as SIS, though, helps to highlight the social aspects of language, as well as shifting us – in Charles Taylor’s terms – from a designativist view of language to an expressivist or constitutive view.

I’m going to focus on Castoriadis’s idea today, rather than trying to bring out the similarities and differences between the two; partly because Taylor is very much focused on producing a correct theory of language, and Castoriadis has already moved his focus further – towards considering how we create the world that we live in.

In the example I just gave, it might be fair to say that I’m accepting that the word literally cannot be confined to a box that literally means literally, but lamenting the lack of clarity that (sometimes) ensues.

To introduce another field of signification – I recently saw a post about the so-called Atheist Bible which indicated (signified?) that some Bible-believing people are of the view that all of us must fit into a box defined by the adherence to one authoritative script or another. These people apparently cannot imagine a world in which some people lead their lives without a guide book.

Jews have the Torah. Christians have the Bible. Muslims have the Q’uran. And it is simply inconceivable that people who call themselves Atheists do not have a similar rule book. That would be like baking a cake without a cookbook! Like, who does that? So they must (and do) have a book, and it must refer to a supreme being – cos, like, where else can you get your laws? – and since that supreme being is not God, it is (d’uh, obviously) Satan.

This is a very box-bound world view.

I mentioned that Castoriadis understands the signifier God to refer to a socially functional conception. Its primary function might be seen as providing the foundation, the grounds, or the justification for a set of rules or laws. That’s what I was jokingly referring to above, about Satan in the Atheists’ bible – some people cannot accept a set of laws or moral precepts that are not grounded in the authority of a Supreme Being. Most of you would be familiar with the challenge that atheists cannot possibly be moral actors if they do not fear the retribution of God – that is, without fear of punishment, why would you behave like a decent and considerate person?

I’m getting ahead of myself – for that’s the basis of a different point in his thinking, about taking responsibility for the laws that we create. But it connects us to the point that the laws that we create are social imaginary significations, and they are intertwined with a much broader set of significations – although this intertwining is in many respects more cloud-like than box-like. Having said that, the next points could be hard to follow if we get too attached to trying to figure out whether we’re talking about clouds or boxes.

Castoriadis uses the term magma – invoking the dynamic moving flowing qualities of a field of molten lava. This can help us to imagine something that is flowing and dynamic, which can intermingle with other things; and which can also solidify – locking in particular sets of relationships. But we have to leave that imagery if we are to grasp the capacity for that solid to rupture, becoming fluid and beginning to flow again.

Anyway…

Among the most important social imaginary significations, for Castoriadis, is the collective itself. Castoriadis observes that before the Greeks created democracy, societies were organised around particular families or places, with leaders who often claimed authority from a god or gods. Such a collective might build a city, or a fortress, and begin to imagine themselves as identical with that piece of land, that place. As most of you know, the First people of Australia identify their distinctive mobs with various places – but not bounded territories so much as places of spiritual significance.

One of the important moments in the Greek breakthrough, then, was to identify the demos as a collective of people who have come together for the purpose of self-government and defense – a collective of free men [yes, they were all men] bound together by choice, who decided collectively on a set of procedures for making and changing the laws, and who agreed that the bases – the grounds, foundations, authority – for these laws lay in their agreement to live by them.

Some 20 years after Castoriadis started to publish these ideas an anthropologist named Benedict Anderson made the basic idea very famous in a book titled Imagined Communities. Anderson pointed out that a nation-state like Australia is comprised of millions of people who will never meet and never have any direct interaction with one another, yet all share an idea that they are bound together by particular customs and laws as well as, in some cases, a language, and many other things.

The patriotic or nationalistic allegiance to an accident of birth is a very formative imaginary connection – a constitutive connection. People are willing to kill and die in defence of these imagined allegiances, these imaginary associations. Our democratic election cycles demonstrate that modern Anglophone societies are increasingly divided, increasingly polarised. Yet for many of us, what makes something like Tony Abbott’s notion of Team Australia so noxious is that it offends our own ideas of what Australia is. It makes a mockery of the Australia that we love and the values that we might be prepared to defend.

More generally, Castoriadis shows that we create the world of our experience through social imaginary significations. He refers to this creation as the Imaginary Institution of Society – the title of the book I showed you at the beginning of this discussion. These institutions include family, community, social norms, offices of government and education, for examples.

All of our social institutions exist because we agree to their existence – and to their existence in these particular forms. Granted, the social divisions that I’ve just described revolve around differences and disagreements about the forms, roles and proper functions of these institutions. Fortunately (I think) like the ancient Greeks, one of our most prized institutions is the set of procedures and practices for debating, arguing, and changing these institutions. But let’s leave that and focus on a specific example to get a better understanding.

Schools exist because societies institute sets of rules and practices that constitute schooling. In some cultures those practices include religious instruction. In other they involve rote learning. In others critical enquiry is encouraged. But in all of them, schooling serves the function of teaching children the rules and practices – the social institutions – of the society. And in the process, each of those separate psyches is itself instituted – to become the kind of social person that constitutes this particular society.

In this vein, Castoriadis has argued that sociology has been pursuing the wrong question when investigating the relationship between the individual and society, because the individual is always already the society. The correct question is about the relationship between the psyche and society, to better understand how the society institutes psyches to become particular types of social individuals.

This insight totally upsets the apple-cart in the dominant Anglo-sphere today – it is anathema to the ideology of the autonomous individual who is the primary site of consumption and self-development in a consumer society such as ours. It says that you are not innately an individual, but instead the product of a society that individuates. Which of course gets very convoluted – for in fact you are an individual because you have been instituted by a society that individuates. That upsetting bit is the idea that you are a product of society, not a unique center of divine light (or whatever other characterisation you have ascribed to / been instituted by).

That last qualification is where it starts to get very complicated – especially in a mass and diverse society like ours. It turns our attention to the intersection of the social imaginary and the radical imagination/ psyche. Flash back to the imagery of the psyche as a cloud with inputs. All of those inputs are either sourced from or shaped by the social imaginary. We spoke briefly last week about a vocabulary for emotions. We discussed how having different words and ideas for our emotions changes our capacity to feel them, to experience them. By implication, that changes our experience of our interactions and encounters with other people and things. Do I need to repeat that such a vocabulary, being language, is SIS? Someone pointed out that such a vocabulary is only helpful if we have people to talk to who share that vocabulary. In the terms introduced in this discussion – these are people who can imagine the emotions in the same forms, shapes, magmas, movements.

As discussed last week, we have a different experience of our emotional life when we have a richer vocabulary with which to describe it. This is a case in which language is constitutive of experience. Taylor and Castoriadis agree that the world as we know it is constituted by what Castoriadis calls social imaginary significations – which, like the subsets language and society, pre-exist any individual. They are here when we enter the world. We can interact, change, perhaps even add to the magma of SIS, but they will most likely survive any particular individual. By the same token, 40 years from now, no-one is going to understand my lament about the confusion arising from the changing meaning of the word literally, for it will literally mean something else.

Another issue that Castoriadis has with the SIS god, besides it being used as an external authority which undermines our responsibility for the creation of our own laws, is that it also serves to deny our creativity more generally. According to the Judaeo Christian tradition, god created the heavens and the earth and all of the creatures and so on and so forth– most of you know this story better than I do, probably – and from this, all of creation was determined by something outside of us; something that also determined us, our nature, our laws, and so on.

As discussed, for Castoriadis, the most important examples of creations are societies themselves; and the most compelling evidence in favour of the idea of human creativity, as mentioned, is the diversity of cultural responses to social organisation.

In his Revisionist History podcast Hallelujah (ep.7) Malcolm Gladwell Discusses two very different modes of creativity in the arts, beginning by contrasting Picasso v Cezanne, then drawing parallel contrasts between Bob Dylan v Leonard Cohen. The contrast may be a little bit overly simplified, but what he’s trying to draw out is a distinction between young creative geniuses who conceive of an idea and execute it almost fully formed, in contrast to other artists who struggle and experiment are not really sure what it is they’re trying to express until after many iterations (and even then, sometimes more is required). He presents this contrast through the terms coined by the economist David Galenson: Conceptual Innovators vs Experimental Innovators.

Gladwell tells a story of a meeting between Bob Dylan and Leaonard Cohen, when Dylan told Cohen he really admired the song Hallelujah, and asked how long it had taken him to write. Cohen said 2 years, and asked in turn how lng Dylan had taken to write XXX (I can’t clearly hear the song’s name, but it must be an important one in the Dylan collection) and Dylan replies “15 minutes”. It later turns out the Cohen was fibbing – he spent more than 5 years on Hallelujah. He recounts times when he was banging his head on the floor because he couldn’t figure it out.

And even then, it wasn’t very good. His producers refused to release it – they said it was crap. He went to an indy label and released it. One critic called the original “so hyper serious that it’s almost satire”. Cohen continued working on it, changing verses, and pace, and playing it live.

John Cale (Velvet Underground) heard it live in NY, asked Cohen for the lyrics. Cohen faxed through 15 pages – 85 separate verses. Cale had to choose which verses to use, and ended up choosing different ones than he had heard Cohen playing – choosing a combination of cheekier and more biblical lyrics than in Cohen’s original recording. Cale also changed some of the lyrics, as well as the overall theme. That recording didn’t sell a lot of copies, but Jeff Buckley heard it. And covered it. His version was brilliant. And thus, the song that we all know and love is a cover of Buckley’s cover of Cale’s cover of Cohen’s original. And that includes later versions by Cohen that we now love and respect.

Gladwell suggests that Dylan, like Picasso is a Conceptual Innovator, and Cohen, like Cezanne is an Experimental Innovator. The reason I suggested earlier that this contrast is perhaps overdrawn is that you’ll find collections of Picasso’s that are in many respects a series of studies on a theme as he tries to get to the heart of the concept that he is trying to express – much like Cezanne. And we find that, like Hallelujah, some of Dylan’s greatest work only reached its full potential when someone who could sing did a cover of it. Nevertheless, it is worth considering these two categories of creativity in somewhat more detail – not because it tells us anything important about the creative geniuses who we all admire, but because it provides us with some practical insight into creativity of the sort that we are personally likely to be involved in.

More to the point, I go into all of this because I think too often young people become discouraged at our own creative endeavours because we compare ourselves to the young genius of Picasso and Dylan – and if we can’t just whip out a masterpiece, we get discouraged and decide to give it up.

When I was much younger I knew several people (some of whom I still know) who were quite gifted musicians or artists who made the “pragmatic” decision that since they were not going to be greats like Picasso or Dylan, they should put those childish dreams aside and focus on a real job – in real estate, or airline administration, perhaps.

In sharp contrast, although I was always a voracious reader – and therefore the thoughts of writing were ever present – I never felt that I had the capacity to spin a yarn, and never dreamed of writing. When I started university in my 30s, I wanted to hone my skills so I might be a competent editor one day. But I slowly discovered some writing talents, although much more like Cezanne, or Cohen – not that they’re artistic, and certainly not genius – but like Cezanne, I often start out with a vague idea of something needs to be worked out. In fact until very late in writing my PhD thesis, I could only write when I was trying to work through a problem. Once I had reached a conclusion, and was satisfied with that conclusion, I had nothing else to say. I mentioned this to supervisor at some stage, and was told that eventually I would have to learn to write about things that I already know.

That process took me through my late 30s and most of my 40s. In my 50s, I can finally write things a bit more spontaneously – maybe it took that long for me to learn enough to know what I am comfortable to write and publish. But even then, they’re never fully formed – and they’re rarely finished before I have had a chance to discuss them with one or three of my dear friends who are prepared to read drafts and provide feedback.

That’s enough about me. What I’m trying to say (following Castoriadis) is that human beings are all intrinsically creative – whether we make one of the great art forms, or we simply decorate our house, do some craft work or dress ourselves in op shop chic. The arts – the so-called High arts – have distorted our views, such that we often dismiss or overlook the creativity of tradespeople, craft workers and even a whole swathe of problem-solvers. Some accountants and solicitors are incredibly creative in finding ways to work around existing tax laws, for example. Maybe that’s not to be encouraged, but it has to be recognized for what it is [yeah, I know, the corporate world does encourage it, by recognizing it very lucratively – far more than the vast majority of people working in the high-arts.]

The main points that I’ve been trying to get across is that the imagination is the primary cognitive faculty of the human psyche; the human psyche has a huge surplus of cognitive / imagining capacity which is defunctionalized; such that we are essentially a creative animal. We create to live, and at our fullest potential, we are living to create!

[1] ‘The Discovery of the Imagination’ in World in Fragments, p.213–245.

[2] ‘Social Imaginary Significations’ in Cornelius Castoriadis: Key Concepts p. 33