Philosophical questions frequently arise in yoga classes and workshops. But the classes move on and the workshops have a different focus, so they are not always the right place or time to pursue these question. This series has been designed to create a space for such questions. The main focus in this (first) series will be on questions of self, identity, setting intentions and seeking balance between effort and surrender.

At the same time, my academic work is in contemporary western philosophical responses to these and related questions. For the past few decades I have been seeking a balance between ancient and modern teachings, all as part of an effort to make sense of living in the modern world.

In this first session I want to begin by briefly outlining a theory of the self that I will work with and develop throughout this series, but also to begin to tease out the tensions between ancient authority and modern inquiry.

- Dialogical aspects of the self

- Answering the question “Who am I?” / “Who are you?”

2 – Differentiate between ancient authority and autonomous enquiry

- Guru/student relationship

- Pick-and-choose

- What are our options?

Let’s start here, and then I’ll develop it further as I explain its similarity and differences to some of the ideas of the self that we find in ancient Indian thinking. The theory that I’m presenting here was developed and promoted by a Canadian philosopher named Charles Taylor, a lovely gentleman who is still writing and speaking in his mid-80s today. You can find him on YouTube, speaking about his more recent work. The ideas we’re exploring here were developed in the mid to late 1980s and early 90s. For clarity, I’m going to dispense with the usual academic practice of attribution and citation, and just outline the ideas in a way that I find useful.

Essentially the self that I am presenting is a narrative construct. It is a narrative that is constructed in dialogue with others – and unavoidably so.

- Constructed in dialogue with others

- Answers unavoidable questions:

- “Who am I?”

- “Who are you?”

- Provides a place to stand

What is a narrative? It’s a story. I’m talking about a story that we tell ourselves, and a story that we tell others. A story that we tell ourselves and others about who we are. A story constructed to answer some very basic yet unavoidable questions – most obviously “Who are you?” This is a question that we encounter in one way or another every time we meet someone new. The stereotypical Australian opening line at a party: What do you do? Is a variation on “Who are you?” When we were kids, we were asked “what do you want to be when you grow up?” which is a different way of asking “Who will you be?”

It really is that simple. Except – yeah, you’re already seeing that you are not reducible to your answer to the question “What do you do?” And it’s further complicated that we answer the question differently – we tell a different story – to the different people that we meet. One frequently cited example in this line of thought is that you present yourself differently to your mother, a police officer, your best mate, and someone you’re trying to chat-up.

This raises a question about whether all of these are different versions of the same story – different parts of a complex but overall coherent story – or are we all many different people? Walt Whitman famously observed: “I contain multitudes”, suggesting that we really are many different people. Yet there seems to be some coherence, some consistency, some cohesion. I can tell my best mate about my last phone call to my mother, the yarn I spun for the police officer, and the image I painted for that girl I was chatting up at the pub. That is, there is an “I” who can tie all of these different aspects together – who might try to make sense of the multitudes that she manifested during the day as she looks herself in the mirror while brushing her teeth before bed.

You might be wondering, are we talking about the narrative or the narrator? I’m not sure there’s any merit in trying to make this distinction – because with rare exception, in most cases this “I” actually buys the stories that she spins; and most especially buys the idea that she spun them, she told the stories about herself. And for the most part, most people most of the time, believe that the story that they are telling – regardless of the variations – are stories about someone or something who is real, who has substance, who matters. Someone who was born in this house or that hospital in that town or this city. Someone who grew up with these parents or in that home, and went to a particular school for a real number of years, and had these experiences and became who I am today. In a very real sense, the story I tell is my story – it’s the story of who I am. And I am nothing other than that story.

We construct this narrative in answer to the question “Who am I?” and we must answer this question / must construct this self, in order to be able to figure out where we’re going, what we ought to do next. Using a spatial metaphor, if I want to get from A to B, from here to there, I must have an orientation in space. If I want to get from here to the pub after this discussion, I need to have an understanding of the relationship between this place and the next. For you to get home, you’ll need some sense of how you got here. Or where here is in relation to your home.

Likewise, if I want to know whether to take this job, accept that invitation, sign that petition, vote for this candidate or that, I need a sense of who I am, what I hold to be valuable. I tell myself a story about my values and how I came to them.

This story is always and unavoidably constructed in dialogue with others. I’ve already mentioned that the story is narrated in answer to the others’ questions. But there are also important ways in which we adopt bits of the story from our cultural milieu. For just one example, those of us who identify as yogis do so in a cultural context in which it is OK for white western middle class people to identify as yogis – even while some of us struggle with questions of cultural appropriation, and colonialism etc. If we do struggle with those questions of identity, though, it is in no small part because those questions exist in the culture in which we find ourselves. [I’m not sure that Thai or Cambodian yogis struggle with questions of whether their practice is cultural appropriation, for example – their struggles lie elsewhere {although authenticity of practice might be a dilemma that they share with us, and still it will be experienced differently}]

To make this more relevant – when we tell our mother, the police officer, our mate and the person we’re trying to pick up different stories, we do so with respect to cultural scripts. Yes, we encounter people in our society who have little regard for the cultural sensitivities and values of others – but it’s very rare to find someone who totally disregards all others. For the most part there is someone we aim to please – or, at the least, aim to avoid having conflicts with.

One of the important things we’ll deal with in coming weeks is the way these stories can change, how we can change them, how we adapt to changing circumstances, and how those changes affect the ways that we see and deal with others.

For now, let’s turn to have a look at how this idea of the self compares to some of the ones that we find in Indian philosophy.

- Atman

- Brahman

- Self / self

- Spirit

- Soul

- Personality

- Character

- Ego

In this list of terms, there are some overlaps, some terms that in certain contexts are used interchangeably; some that have different meanings in other religious contexts; and some that derive from modern psychology. I am not really interested in trying to pin down their exact definitions and distinction, or what, for example, the Vedic or yogic idea of the self is—in either its dualistic or nondualistic formulations. But neither do I feel a need to reject them outright – I think they are useful metaphors that can help us come to grips with what we’re talking about.

Among them, the one I am most familiar with is the Buddhist idea of the self as an ego-construct. As an ego-construct, it is understood to be an illusion, or maya. Central to Buddhist philosophy and practice is the idea that being attached to this ego-construct, this sense of self, is one of the primary sources of suffering. One way to put this is that the desire for it to be real, the desire to protect it – to protect its integrity, its reputation, its possessions – is to chase an illusion, which is ultimately and inevitably unsatisfactory, disappointing; this desire is considered to be the cause of much of our suffering. Hence, letting go of these desires, practicing non-attachment to this sense of self, is understood to be a necessary stage on the path to enlightenment – which in the simplest terms is merely the cessation of suffering.

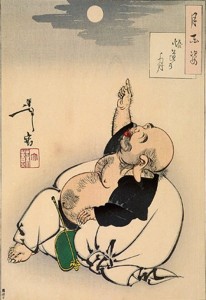

From what I can gather, with important but subtle differences, the other Indian conceptions of the self are not far removed from this. Yes, some of them say that our attachment to this ego-construct is an obstacle to realizing our true nature, as One with the Atman or Brahman (that’s what is depicted in the image here). That is, it distracts us from realising that all is one, and that we are integrated in the divine cosmic whole. I will try to address this concept in more detail next week.

One of the main points that I want to make about these older concepts is that they are not at odds with the theory that I am presenting, at least in terms of who does the constructing, how it is constructed, and what we can or might do about it. Or rather, they are not any more at odds with the idea of the narratively constructed self than they are with each other. Certainly there are some very important differences in the ethical prescriptions of what we ought to do about it, as well as some other finer points that we might explore later. For now, let’s turn to the differences between trying to follow an ancient tradition and trying to construct a modern approach of our own.

Following an ancient tradition

Following an ancient tradition

- Is this even possible?

- Pick-and-choose

- Crows gathered at the sacred grounds

There are at least two quite different modes of being, and different modes of learning. When we learn from authority, we find someone who knows – an authority figure – and we accept what he tells us is true and correct. Without question, without challenge, without being smart alecky little upstarts who think we know best. The alternative is at the heart of the scientific method – it doesn’t mean smart alecky little upstarts – but it does mean that when we encounter truth claims we critically engage with them, testing them against our experience, against the available evidence, testing to see how they fit into our world-view, to what extent they help us to make sense of the world around us.

There is a strong tradition – in yoga, and in every religion – towards authority. The ancient style of knowledge transmission was for a student to devote himself to a guru, surrendering his petty ego to the superior knowledge and experience of the teacher, and doing what he was bloody well told.

In the yoga tradition, students who would shop around for a teacher, picking-and-choosing teachers and titbits of knowledge were called “crows gathering at the sacred grounds” – that is, they were seen as scavengers picking at scraps, rather than devoted and disciplined students.

We still see a yearning for authority today, both in the yoga studio and elsewhere. For example, I heard a yoga student ask the teacher “But all we’re trying to do is follow what those guys did in a cave 3000 years ago, right?” She thinks those old guys worked it out, and thinks we’ll be on the right path if we can just learn what they taught us.

I understand this is still the predominant mode of teaching in Catholic primary schools too – just do what you’re bloody well told, and you’ll be good with God, ok? That’s also the primary mode of instruction in the born-again and evangelical cults in the USA and Australia – there’s space for critical enquiry, no grounds for questioning. Just learn the truth as it is presented to you both those who know.

The point that that student was missing is that what those guys did in a cave (or a forest, or a savannah) 3000 years ago was to work it out, to experiment and figure out what works for them, in their particular context. They may have discovered some things quite profound, and maybe they even managed to pass that on to their students, who in turn passed (some of) it on to their students, and then eventually someone attempted to write it down in a book, that has since been transcribed, translated, interpreted and passed on down until some of us have had the privilege and pleasure of studying the English edition – perhaps with a commentary by some 16th or 19th century sage / guru.

That text, though, is not what those guys figured out in a cave 3000 years ago – it’s just a pointing towards… The Buddha’s oft-cited observation about the difference between the moon and the finger pointing at the moon is fundamental to everything that we’re going to talk about in this discussion series. “When I’m pointing at the moon, don’t look at my finger!”

Much textual debate amounts to arguing over the size, shape, texture, colour and direction of the finger. Why didn’t he cut his fingernail? we ask. “Why didn’t he wash his hands?” “Is that a real tan, or a spray tan?” we wonder. These are questions that distract us from encountering the moon; experiencing the moon, figuring out what the moon means to us.

And if you’re now trying to figure out what the moon has to do with us, you’re looking at the finger again, so to speak. The moon is not our issue – merely an example.

Almost everything that we’ve been talking about is metaphorical – metaphors are pointers; fingers pointing at something that we cannot directly touch, feel, weigh, measure. If I use words like love, anger, regret, I’m pointing at different emotional states, which we sometimes call feelings. I’m pointing at so-called feelings that I assume (I can only assume, I have to assume) that you have an experience of. You cannot feel my feelings – you cannot feel my toothache, or the pain in my knee. But because you have had similar experiences, similar feelings, you can perhaps sympathise – or at least identify with what I’m trying to express when I talk about these things.

Shifting focus a little, we cannot begin to try to follow a tradition until we address the question: which one? Even if we narrow the question down to “yoga”, for argument’s sake, there is no one tradition. Today we are confronted with Hatha, Iyengar, Ashtanga, Bhakti, Bikram, Tantra, Vinyasa Flow and on and on and on – and we know that despite their claims of ancient lineage, many of these are very new inventions. But when we look way back we find as many competing approaches and views.

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras has become the go-to book for ancient roots – it’s not quite 2000 years old. But there were already divergences and differences in yoga practice 1000 years earlier. Even leaving that little detail aside, one of the things I find most striking about the way yoga is taught and practiced around this neighbourhood is that Patanjali’s eight limbs of yoga are presented as the guiding principles – the way, to borrow a Taoist term. And yet, Patanjali’s dualistic philosophy is largely ignored; nondualistic philosophy is taught in its place.

I go to festivals and retreats where I learn that the ancients advocated that I should surrender my small-s-ego self to the big S Brahma Self or Atmān – because yoga means union – it means union of my small self with the universal Self. (That’s what was depicted in the image on the previous slide.) But that’s not what it meant for Patanjali – he may have been thinking of yoking or uniting something – but in his dualistic philosophy, you and I are radically separate from the Divine Spirit – however that’s conceived. Radically separate and never to be united.

I need to be clear – splitting these hairs is not my area of expertise – nor am I overly interested in them. My point here concerns the comment about “crows gathering on the sacred ground”? This is a way of disparaging those who would “pick-and-choose” their philosophical points, their sacred insights, the twists and turns along their spiritual journey. Such disparagement is a way of controlling knowledge, a way of controlling others, of restricting, limiting, curtailing enquiry.

It’s not my way – but I recognize that for some people it’s a temptation – a friend of mine used to chant “freedom from choice” when confronted with an overladen menu, or a supermarket aisle. “Just tell me the truth and I’ll be satisfied” is an understandable yearning. Understandable, but delusional. I couldn’t tell you the truth even if I knew it. I could only try to point to it – you still have to realise it for yourself.

That in itself doesn’t undermine the authority of the guru – but with so many competing sources pointing in different directions, we modern seekers of the truth have little choice but to pick-and-choose. It has been that way for a very long time. That is the understanding that lays behind the French philosopher Renee Descartes’ development of the earliest principles underlying what has become the scientific method.

Descartes is held responsible by many post-modernist and feminist thinkers for much of the misguided rationalizing of modern thinking. And rightly so. But it’s essential that we do not throw the baby out with the bathwater. If we keep that in mind, it will be easy for us to see a place for Cartesian doubt in our witnessing meditation practice – when we get around to it!

Descartes was faced with a similar situation to our own. Growing up in a society in which the collected knowledge of the ages was available in books, he pondered how he was to determine which knowledge or truth claims were correct. We needn’t go through his full ponderings – suffice to say that he decided that he could not rely on any one’s authority to adjudicate between competing claims, so he was going to have to test them against his experience, or against empirical evidence.

At its best, I think that’s what we do in modern yoga, too. We can read the ancient texts, we can be guided by teachers and gurus and so on – but ultimately what matters in our practice is what works for us. We are picking and choosing, we are guided by people in whom we place our faith, we follow their leads, heed their advice, etc – but ultimately, each technique, each practice, each insight must be tested against our own experience.

For just one example – a year or so ago I injured myself; I think it was doing a shoulder stand. I already had a fraught relationship with shoulder stand, and after this incident, I stopped doing it. Whenever a teacher instructed shoulder stand, I did something else. But recently a teacher called me out on my “aversion” to shoulder stand, and suggested that maybe I should try to get over it. In our next class, when she started talking about setting up for shoulder stand, I set myself up for it. Fortunately there were only a couple of students in the class at the time, so she came over and helped me into it, and through it. I didn’t love it, but I didn’t hurt anything either – so I have begun practicing shoulder stand again, observing its effects, observing my reactions and so on.

I didn’t do it because I was told to, but because it was suggested by someone I trust. I didn’t just bang it on either, but entered into it consciously, thoughtfully, carefully.

Different people are at different stages in their practice (of yoga, of self-enquiry, of personal growth), and in their self-confidence. And some of us were educated to not only submit to authority, but to seek out an authority to whom we can submit. I’ve had students like this in my classes at university, and I’ve witnessed them in yoga classes – they just want someone to tell them what to do, tell them the one true way, the one truth, what is right and what is wrong.

I can’t do that, and I won’t try. My favourite teachers are the ones who are trying to work it out, and who respect that each of their students is on their own journey. My favourite philosophers are the ones who understand that they are merely pointing at the moon – and their reader must find their own way of getting there. And I cannot adhere to a philosophy of the self that maintains that there is one absolute truth, and that dictates that my path must be to find that one true path, that one absolute truth.

The philosophy of the self that I’m working with is one which sees that we each construct our self as selves in stories that we tell to ourselves and others – stories that are specific to our contexts and experiences – stories that respond to our histories, cultures, societies and dispositions.

I don’t want to disparage any of the ancient ideas, or dismiss the values that are conveyed in them. But I do think there’s a real risk that in our (necessary) picking and choosing many of our guides have become rather selective in what they’ve chosen, and they manage to do us a disservice in presenting a skewed view of who we are and how we should live. Let me briefly outline one of the ideas that I am most familiar with, by way of both tying the ancient ideas into the modern theory of a narrative self, and opening up some of the complexities of what we might discuss in coming weeks.

Buddha Nature / Love and Light / Multitudes

In Buddhism we find the idea that we all have an essential Buddha nature. The Buddha is not a god or deity, not a spirit or daemon – just a man who found enlightenment and provides a glowing example for each of us of how we too can follow that path. The Buddha nature is the “pure, undefiled mind” – not defiled by lust, attachment, fear, etc. We can find fearlessness by surrendering our attachment to material possessions and our petty ego-self.

This is all well and good as guiding principles, as an ethical framework that we might aspire to live up to. But it is dangerous nonsense if it leads us to live in denial of the daemons that burn and rage within our multitudes. Please don’t get me wrong – I am not suggesting that the Buddha himself made this mistake. Nor do I think many dedicated Buddhist scholars or teachers make this mistake. But among those of us who pick and choose, like new age consumers in the spiritual supermarket, it is quite common to hear distortions of this message that sweep the multitudes under the carpet, preferring instead to embrace a self-image that is only love and light.

As the wonderfully blunt Alana Louise May put it:

“Love and Light” is a term commonly used by New Agers that is flung around like some kind of coverall, sweeping whatever has come before it in its passive aggressive fluorescent light.

Open your mouth and allow me to shove my love and light down it, lest you take offence, lest you think I am a bad person, lest you think I am anything but angelic.

… the real aggression is aimed at one’s own shadow.

“I am only love and light. All I am is love and light.”

There is nothing that could be further from the truth and you are completely delusional and disregarding one half of yourself.

Your shadow works its fucking ass off to get your attention so that you may learn something of value.

“One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light but by making the darkness conscious”– Carl Jung

This same vapid half-truth can be extracted from any conception of the spirit or soul as a divine and or immortal entity. Whether it is one with god, or a manifestation of the divine energy or any of a myriad of other conceptualisations, there is a tendency for the celebration of love and light to lead to the denial of the shadow and shit that are equally constitutive of who we are.

We also find this in some Christian portrayals of a flesh-encased vehicle for an immortal soul, created in god’s image – with our sins and shortcomings attributed to external forces – devils, demons and other temptations. I’m all love and light, except when I’ve been led astray, they say.

The line from Jung that May quotes gets to the heart of the matter – it is only by delving into the darkness, in bringing it to light, recognizing it for what it is, and acknowledging that that is who we are (too), that we can begin to move towards the light. In fact, the flip side of this is that if we simply move towards the light, the shadow grows and clings. There’s a brilliant sketch illustrating this idea in one of Jung’s books—but of course I can’t find it on google. It’s a simple sketch of a man holding a candle, using it to light the way ahead, while casting a furtive glance over his shoulder at the shadow that is following him – his shadow, of course, created by the candle he’s carrying in front of him. We can imagine that as he begins to run away from his shadow, the extra movement causes the candle to flare brighter, which causes the shadow to loom larger.

At its best a witnessing mediation is a technique for examining the shadows. An effective psychotherapy is also a technique for coming to terms with the shadow. Freud proposed that the guiding principle of psychoanalysis is to bring the unconscious into consciousness – which Jung transposed into bringing what is in the shadow into the light.

This is not going to become a discussion of either Freudian or Jungian psychoanalysis, although some of their basic concepts, such as the unconscious and conscious, are incredibly helpful to understanding what we’re dealing with. We’re going to talk about the narratively constructed self, but this construct is not adequate to contain, express or define the multitudes that I am. Much of who / what I am remains in shadow, in my unconscious. Oooooo – except from time to time when it arises to shape my behaviour, leading me to act out in ways I really rather wouldn’t – or maybe I would, but I could do it more effectively, and less harmfully, if I was aware and accepting of the tendency / desire to act in that way.

It’s also worth mentioning that there are a wide variety of ways that the word self has been used and defined in psychology. I’m not going to begin to pretend to be across that literature. Suffice to say that my random encounters with these concepts lead me to conclude that like much else in psychology, there is much too much emphasis on trying to pin down precise definitions, splitting very fine hairs and forcing things into precise categories. Of course some philosophers are also that way inclined – but that is not my way.

As I said earlier, much of what we will be discussing is metaphor. I’m not sure that’s the best term to use to categorise the self, but when we discuss the self, or a self, we’re talking about something that no one has ever seen; its existence can only be deduced by inference from secondary effects. It certainly cannot be objectively measured or assessed. Of course this is also the case with the psyche; and the spirit, the soul and many other ways we have of speaking about what goes on within, and what drives, the human person.

Before wrapping this up, let me make a few pointers towards our next conversation, specifically about how this idea of a narrative self can be employed in our self-enquiry and self-transformation. In the simplest terms, it is probably already clear, we can simply change the story I’ve used this big-picture example of how getting caught up in misleading spiritual frameworks can lead us into emotional bypassing. In those cases, it’s obvious enough how we might set about going deeper into the philosophy or spirituality underpinning it, and get a better understanding of what we’re talking about – as I’ve already done by observing that spiritual bypassing is not a result of the spiritual tradition itself, but of a misreading of it.

Next week, though, I want to look at some of the more micro-level, more personal narratives that hold us back – the stories we tell ourselves about not being good enough, about no-body loving us, etc – and begin to talk about some of the re-narrative techniques that are used for shifting these frameworks so as to give us a more empowering orientation.