Charles Taylor’s theory of the narrative self, which we discussed in the first couple of weeks, is developed from a hermeneutical orientation. This orientation entails something like the Socratic dictum ‘know thyself’. Better and clearer interpretations of who we are, in a sense, have instrumental value for moving us closer to the experience of fullness (Taylor, 1985: 15–57). In one form or another, this perspective of ‘self-improvement through knowledge’ is a common theme in philosophy, both Western and Eastern.

This week we’re going to focus on better understanding our selves as embodied beings.

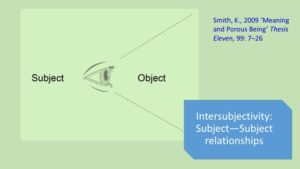

We started to discuss the subject:object relationship last week, looking at the ideas of the Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Someone observed that the subject:object distinction seems to be much sharper in English than in German. We noted that Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology is French, though, and builds on the work of the German philosophers Husserl and Heidegger.

The ensuing conversation focused on relationships between two people – on the ability to communicate our emotional states or “inner worlds”. This got me to thinking that perhaps what she meant was that the German language allows for a greater sense of “intersubjectivity”.

The idea of intersubjectivity is central to phenomenology (the philosophical orientation of Merleau-Ponty, Heidegger, and a significant influence on Charles Taylor). We have touched on the idea of intersubjectivity a few times, without mentioning it. It is one way of trying to explain the mystery of the baby smiling in response to an adult’s smile (we heard other attempts last week, but they were of the type that is actually explaining away a phenomenon, rather than explaining it—that is, when we cannot explain something within our dominant paradigm, we are inclined to find ways of making the problem go away. For example, Taylor discusses how certain materialist philosophers have “explained away” consciousness, since it cannot be accounted for within their philosophical schema in this cbc podcast).

I return to this slide because we didn’t get where I had intended to go last week; but now I’ve introduced a new concept, it’s going to take us in different directions – one of which, if we manage it properly, will bring us back into a yogic discussion; specifically linking the idea I mentioned of being ”not only a flesh encased ego” from transpersonal psychology with the yogic understanding of the koshas.

[The next few paragraphs are extracts from an article I published on this topic in 2009: ‘Meaning and Porous Being’, Thesis Eleven no.99. As extracts, the paragraphs read more as bullet points than as a linearly constructed argument.]

“Taylor argued in his early work that meaning is always ‘for a subject, in a field’, i.e. that meaning is always socially contextual. He suggests, quite explicitly in A Secular Age, that some meanings at least are non-anthropocentric, pre-subjective, extra-social – meanings that are meaningful independent of human interpretation. While this approach is as problematic as it is familiar when extended to include extra-social grounds for the social order – for norms, laws, institutions, etc. – we might at the same time find that it opens the way to a more fulsome understanding of the human animal.” (p.11)

“In ‘Interpretation and the Sciences of Man’, Taylor outlines three points that must be incorporated in a theory of meaning: ‘(1) Meaning is for a subject . . . (2) Meaning is of something; that is, we can distinguish between a given element . . . and its meaning . . . (3) Things only have meaning in a field, that is, in relation to the meanings of other things’. Anything the human subject can know about an object is known from a particular point of view, a particular subject-position, and any new knowledge of said object affects this subject-position which necessarily affects the knowledge of the object, and thus the social institution of the object as an object.

Meaning is always problematic, in no small part because it is always subject-referring – it does not reside ‘objectively’ in the situation or context in question. But that it is ‘subject-referring’ does not entail that it is merely ‘subjective’, for it is always also in a field and only ‘meaningful’ in reference to this field.” (Smith 2009: 15)

“Focusing on the relationship between meaning and action at the individual level, Taylor argues that the double demand for meaning and action-decisions generates a need for a meaningful framework, or a framework of meanings, with which to orient oneself in the world, within a field of meanings.

Such an orientation is necessary in order for the human subject to ‘make sense’ of its sensory perceptions, of the world it experiences, and of the actions of the other subjects it encounters. In short, Taylor defines this ‘framework of meanings’ as the ‘self’. He argues that the self is constructed as a framework of meanings that provides the individual with an orientation to the world s/he lives in. This notion is firmly located in a theory of expressive meaning – as opposed to earlier ideas about a meaningful cosmos – which means that the self is an expression of a particular (set of) orientation(s) to the world. In keeping with his expressivist orientation, Taylor recognizes that the self, this orienting framework, must be articulated, and that articulation includes action as well as linguistic expression. This understanding is occluded by scientistic epistemologies that categorically reject the validity of subjective evaluations” (p. 16)

These ‘scientific epistemologies’ include Descartes’ search for objective certainty, which set the foundations for scientific validity. Descartes’ framework underpins the distinction between qualitative and quantitative social science research, among other things – and provides the grounds for natural scientists rejection of the social sciences.

“As self-interpreting animals, the way we understand ourselves, how we understand the world that we inhabit, and what we understand to be ‘good’ are fundamental to the way we live, the way we behave, the decisions we make, the actions we take.” (Smith 2009: 16)

“Whereas before, as we have seen, meaning is always for a subject, in a socially constituted field, in A Secular Age Taylor argues that there are some meanings that are, so to speak, pre-subjective: non-anthropocentric meanings; meanings that are meaningful whether human subjects get them or not. At the same time, this development is only new in the sense of its explicitness; it was already implied in Sources in the suggestion that we might need non-anthropocentric moral sources in order to experience fullness.” (Smith 2009: 17)

“Castoriadis criticizes theorists of intersubjectivity for not going far enough towards a truly social conceptualization of human subjectivity, arguing that to speak of intersubjectivity is to continue to try to understand the social world as constituted by individual subjects (1987: 108; 1991: 144), and thus failing to fully comprehend the extent to which said subjects are never truly individual – at least not in the buffered or atomistic sense of the term. The human subject, for Castoriadis, is always permeated through and through by society in the form of the social imaginary. In this sense, it is an intrinsically porous subject.” (Smith 2009: 19)

I mentioned being both a subject and an object. Sometimes one, sometimes the other – perhaps sometimes both simultaneously…

Something similar happens with all of these senses

Put your hands together. Which hand is touching and which is being touched? Can you feel both touching and both being touched at the same time? Or are you shifting back and forth between the two?

This is a good place to segue into intentionality. You can shift your focus from one to the other, intending for the right to touch the left, the left to be touched – then reverse them. I don’t think I can do both at the same time; I’ve spent a lot of time trying, but I always find myself focusing on either one hand touching or one hand being touched.

My article ‘”Deep Engagement”& Disengaged Reason’ doesn’t go into the issues of two hands touching, but into the relationship between objective knowledge and other forms of knowing. It outlines the benefits of Descartes’ method of radical doubt – one of which is the incredible technological progress that has been made since adopting that stance of disengaged reasoning, but also discusses alternatives, among which is the idea that we are more deeply engaged in the world than Descartes’ method assumes.

The mind/body split arises as a response to a perceived problem about how “outside data” gets “inside”, as knowledge. Remember, Descartes was worried about evil genies or demons deluding him with false ideas? In science, psychology and philosophy, a more pervasive concern is: what is the relationship between our inner world and the world around us? Most of the dominant responses treat them as radically separate. As we discussed last week, this makes them dualistic approaches.

Merleau-Ponty’s approach toward embodied experience breaks down that dualism. As Taylor describes it, we begin to know the world long before we begin to conceptualise it. Baby’s don’t stop and conceptualise the world in order to cope – they begin to cope by feeling, grabbing, watching, listening, moving, sticking stuff in their mouths to taste it and so on. Long before we begin to stand back to try take “an objective view” of things, we are thrown into the world and throw ourselves into the world with our whole being.

A disengaged stance to food, for example, might consider its calorific values, its fat content, its nutritional value and so on. But long before anyone thinks about those things, we encounter stuff, smell it, and if it’s not too repulsive, taste it – then decide whether we like it or not. A complete engagement. No separation of mind and body – tasting food is a multi-sensory, fully embodied experience.

Yes, with the acquisition of various concepts and ideas, we might gradually learn to distance ourselves from these sensory experiences, to stand back and make “objectively rational” decisions about what to eat, and how much to eat. But the simple fact that doing so is a continuous and arduous chore for so many people (if not all of us) speaks to the fact that such disengagement is not our default mode of being.

When I introduced Descartes last week I mentioned that he is often blamed for the excesses of rationalization in modern society. Hopefully I acknowledged that that blame is not misplaced. But I don’t think I got around to stating that we have to be careful that we do not throw the baby out with the bathwater. A purely disengaged instrumental rationality is inhuman; but disengaged instrumental rationality broke us out of the oppression of the Church authority, overcame the limitations of tradition, and provided us with all the wondrous technologies that we depend upon today. We need not go all ga-ga about technology; but those who deny that they enjoy any benefits from technology are not being entirely honest with themselves (to say the least).

Many of us who are critical of the primacy of technology, though, extend that critique into a condemnation of disengaged reason that is precisely throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Some feminists, in particular, are this way inclined – but so is pretty much all of what passes for post-modern philosophy. In both cases, the claim is that the over-valorisation of reason is what lead us into industrial pollution and industrialized killing, as well as the objectification of women, colonisation and the exploitation of people of colour etc… The prescribed remedy is to reject disengaged reason and return to a more connected, empathic or intersubjective mode of knowing.

Separate or Connected Approach?

[T]here are some domains in which truths will be hidden from us unless we go at least halfway toward them. Do you like me or not? If I am determined to test this by adopting a stance of maximum distance and suspicion, the chances are that I will forfeit the chance of a positive answer. An analogous phenomenon on the scale of the whole society is social trust: doubt it root and branch, and you will destroy it. (Charles Taylor (2002) Varieties of Religion Today, p. 46)

[the remainder of this section is again extracted from ‘Meaning and Porous Being’]

What I want to retain of the disengaged, instrumentalist approach is summed up in Taylor’s example (told for a different purpose):

“A modern is feeling depressed, melancholy. He is told: it’s just your body chemistry . . . or whatever. Straightaway, he feels relieved. He can take a distance from this feeling, which is ipso facto declared not justified. Things don’t really have this meaning, it just feels this way, which is the result of a causal action utterly unrelated to the meanings of things. This step of disengagement depends on our modern mind/body distinction, and the relegation of the physical to being ‘just’ a contingent cause of the psyche.” (A Secular Age: 37)

The final sentence of this quote goes too far – we need not go as far as to reduce the somatic to psychic causality to acknowledge the fact of psychosomatic conditions – as in the ideal-material framework, the causality goes both ways. But I want to retain the capacity to step back from my knee-jerk reactions and analyse the situations/factors/etc. at hand. The course of action described above is perhaps the most effective response to depression (at least, if depression is something that needs a response). This point becomes clearer if we introduce Taylor’s oft-used example of how identifying that one is experiencing the emotion ‘jealousy’ allows for a better account of the situation – and this better account requires precisely the capacity to disengage.” (Smith 2009: 21)

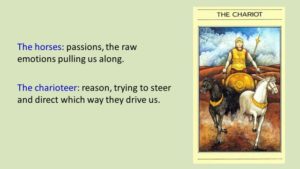

The image of the Chariot used in the Tarot cards is a great ullustraition of the relationship between reason and the passions. Descartes, like Plato, understood reason as a mental faculty for directing the passions – but he recognized that nothing would happen without the passions. Passions drive us, motivate us, inspire us to act – sometimes, as in Achilles’ case, reason (Athena) intervenes (in The Iliad), suggesting a wiser course of action; but even the new course is motivated by the upsurge of passion or emotion

One limitation of using this image is that, in “real life”, horses are disconnected from the chariot when their work is done, and given a rest – but the passions never stop. The passions are a product of the psychic flux [our topic for week 5], an endless surging forth of representations, affects and intentions. The passions are continuously firing, while reason is continuously calculating, scheming, projecting, assessing. These are never-ending, exhausting processes.

These are the ceaseless fluctuations of the mind that Patanjali’s yoga seeks to settle – the point of meditation. They can also be mitigated to varying extents through the use of intoxicants. But such mitigation always remains temporary; when the drugs wear off, the thinking processes fire up again

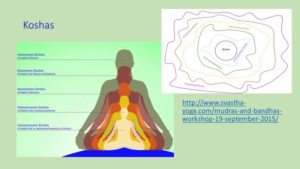

There are two places I can go from here (probably many more, of course) – to discuss the koshas, and the idea of being more than just a flesh-encased ego; or to discuss different Ways of Knowing [remembering that Descartes’ problem is how we can be certain of what we think we know].

[Except for the second paragraph, this section is extracted from a blog I wrote reporting on a yoga workshop on Mudras and Bandhas.]

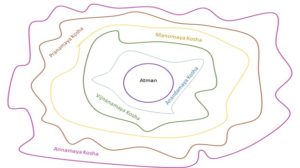

Annamaya Kosha is the outer most, and thus most tangible layer. It represents what we most commonly think of as our physical body. It is referred to as the “coarse body”, in distinction from the increasingly subtle aspects of the body in the other koshas.

[One thing that strikes me about this depiction is that the layers of the onion are the inverse of the imagery we have of auras – which is how I envisaged the message from transpersonal psychology about the flesh-encased ego. In this image of koshas, the flesh-case is the outermost layer – the atman, or spiritual self (Absolute Self) is the inner-most layer. In images of auras, though, the flesh-case tends to be the inner most core, with each of the other “layers” radiating out from there. I’m not sure what to make of that, I was just struck when I realised this image was layered differently than what I initially saw {which is a different point of departure for a discussion about how our precepts and intentions shape our encounter with the sensory world – in this case, I saw what I expected to see, until I looked deeper and realised that the imagery was not that]

Pranamaya Kosha is the next layer, the energetic body. In our asana practice it is frequently invoked as the breath.

Manomaya Kosha is the mental body or mind layer. The mental body is engaged by drishtis, for example – the focal points used in various asanas. Manomaya Kosha is engaged in the process of fostering single-point focus.

Vijnyanamaya Kosha is the wisdom layer and Anandamaya Kosha is bliss body.

Vijnanamaya Kosha is the seat of the Jnanendriyas (entrance doors), which we explored in our Embodied Learning workshop in May. “It is the vehicle of higher thought, vijnana — understanding, knowing, direct cognition, wisdom, intuition and creativity” (http://veda.wikidot.com/vijnanamaya-kosha).

At the center of this schema is Atman, which is variously interpreted as True Self, Spirit or Soul. It’s also understood as the Universal Self. It is from this perspective that non-dualistic yoga philosophy perceives the Self and the Universe as One.

The immediate focus of yoga is the integration or harmonization of the koshas. This integration is the “union” which is yoga.

In this sense, yoga practice aims to move the koshas towards something like the neat symmetrical sheaths depicted above, or even to the more standard view of concentric circles. But what most of us are faced with in our everyday lives is something more like this more messy diagram:

The “dart board” representation of the koshas that you find when you google it is misleading, because we are not rounded. Becoming rounded is our aim, a significant step forward from where we find ourselves. The evenly spaced sheaths of many depictions of the koshas are much too smooth and balanced. Our koshas are rough and uneven. There are different distances between different parts of our subtle and coarser bodies.

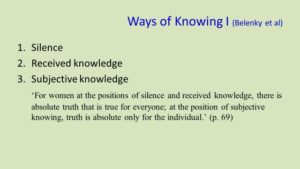

Note that I’ve titled this section “ways of knowing” while the book is titled Women’s ways of knowing. The authors are four American feminist psychologists who interviewed several hundred women (approximately 450 if I recall correctly) to ask them who they know what they know. This is a very interesting study, for it takes the central question of the epistemologists and approaches a “general populace” with it. The findings are, I think, incredibly useful in helping us to understand knowledge, ourselves, and especially the people that we encounter as we negotiate our ways through life.

The authors (see the reference list at the end for their names) are very careful to limit their conclusions to the subject population that they studied – women between the ages of about 18 and 60 (again, if I recall correctly). I think, though, that while some of the findings may be more common among women, their results are more generally applicable. That is, these categories also apply to men, although the proportions of each group that fall into the different categories may differ. For a fuller discussion of this work, see my previously mentioned article ‘”Deeper Engagement” and Disengaged Reason’.

The first type of “knowing” that they describe is Silence: “I know nothing”. People in this category don’t ask questions to either seek clarification or to challenge authority. They don’t believe that their point of view is worth expressing; they expect to be told that they are wrong about any view they do express. Some terms used to describe them are: ‘deaf and dumb’; passive, reactive and dependent (i.e., powerless).

The second type that they describe is Received knowledge. This is knowledge received from an external authority. It includes “expert knowledge”. “I only know what I’ve been told”. They learn by listening. For these people knowledge is seen to be concrete and dualistic (either/or, right or wrong, true or false, good or bad, etc). Such people seek knowledge, but don’t express their own points of view; they don’t participate in class discussions, for example. They believe that not only their own knowledge, but all knowledge is received from a higher authority. They therefore have difficulty with teachers who push them to “work it out for themselves”.

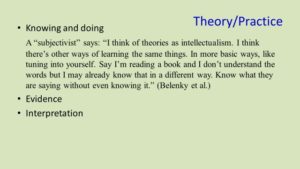

The third type is Subjective knowledge; knowledge derived from an internal authority. “I don’t care what you say, I know my ‘inner’ truth.” The researchers suggest that this position is typically reached by someone who has been subject to strict external authority (as in an abusive relationship, or an authoritarian patriarch or clergyman) and has had some sort of epiphany which leads them to distrust all external authority, to trust only their own “internal” knowledge. Belenky et al call them “multiplists” – they accept that there are multiple points of view (or opinions) about an issue, and “ground” their own opinion on some “inner” feeling/conviction. They might say: “Your truth is your truth. It has no bearing on me. I know what I feel in my gut.”

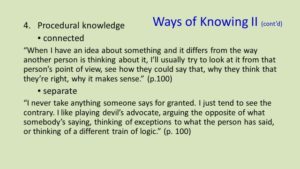

The fourth type of knowledge that they identify is Procedural knowledge, which actually breaks down into two sub-categories: connected and separate knowledge. The authors call this “the voice of reason”: “…they had abandoned both subjectivism and absolutism in some areas of their lives in favour of reasoned reflection.” (p.88) For example, one of their informants, a young college student, spoke about learning to work with her teachers: “In writing an essay…, Naomi learned, you had to do it ‘the way they said’

But you’re the one who’s placing the judgment on it, and as long as you’re substantiating your argument they can’t – they’re not going to disagree with – they can’t – it’s not a matter of disagreeing, as long as you substantiate what you’re saying. They’re teaching you a method and you’re applying it for yourself.

‘Naomi expresses here an important new insight. She realizes that her teachers do not presume to judge her in terms of her opinions but only in terms of the procedures she uses to substantiate her opinions.’ (pp. 91-92).

“The world that procedural knowledge reveals is more complex than the world revealed through received or subjective knowledge.” (p. 97)

The category that they call Separate knowledge corresponds almost exactly to the type of knowledge that we have been associating with Descartes. One way to characterize it is as the Devil’s advocate. The “separation” here is the same as the “disengagement” in the title of my article. In the simplest terms, the basic process is that when I am presented with a proposition, I will attack it from every angle, using every tool available to me to test it, to challenge it, to see if I can knock it down. If at the end of my assault, when I’ve exhausted all of my resources, if the proposition is still standing, I will accept its veracity – at least provisionally; until new resources or new information comes to light, which I might then use to knock it down.

In contrast, Connected knowledge entails what I called a deeper engagement. The easiest way to present this is to say that if you put forward a proposition that I do not necessarily or automatically agree with, I will seek to learn why you believe this proposition to be true. That is, I want to connect with you, to understand the problem or situation in hand from your point of view – to get “inside your head” so to speak, and see the world from your point of view. At the end of this process, I may still not accept the proposition, but I’ll have a much better understanding of who you are and where you stand on matters that are important to you.

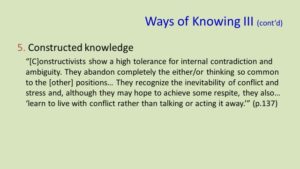

“All knowledge is constructed and the knower is an intimate part of the known” (p.137)

This fifth type of knowledge Constructed knowledge is a combination of the others. It is an understanding that knowledge does not exist independent of those who know. Knowledge is not out there in the world waiting to be discovered, but rather is constructed by the people who discover truths about the world.

The authors of this fascinating study are adamant that they have not presented a hierarchy of ways of knowing, but I cannot accept that. This doesn’t mean that we should dismiss or judge those who are predominantly confined to one or another of the five categories. But we should [and I try to very rarely use “should”] aspire to, and teach others to, move into the realm of constructed knowledge. This in part means learning to use both sets of procedures, and knowing when it is appropriate to take a disengaged or separate stance, and when it is more beneficial to use a deeper form of engagement.

Finally, it’s worth noting that those in the 3rd category – subjective knowledge – have moved there from one of the other ways of knowing; and they moved do to their life experiences and social circumstances. It may seem like drawing a long bow – but I think we can infer from that that the “higher” up the scale you move, the more likely and able you are to move around in the categories. Which also means that no matter how “high” up the scale you are, there are always going to become thing that you know nothing about (silence) and some things that you take on faith because you were told it by someone whom you trust is a valid authority on the matter. In the latter instance, for example, I frequently get on airplanes, placing my faith in the expert knowledge of the aircraft mechanics and pilots who decide whether the plane is safe to take off or not, as I have no first hand knowledge of these matters. Similarly, I sometimes follow my doctor’s advice.

I always worry about sharing this quote with students, concerned that they’ll take it out-of-context. It’s important to read it from the perspective of constructed knowledge a while earlier. I’m a theorist. I believe theory is not only worth doing, but important. Certainly there are many things that we know in very different ways. As wella s being a theorist, I’m a yogi – there is much that I have learned from an embodied practice that I would never learn from books – and there is much that I have learned from books that I’ve only managed to comprehend because I had other, non-theoretical, experiences that informed that learning. At the same time, although theorizing may be intellectualism, I don’t take that to be a “bad” thing – unless it’s empty, ungrounded intellectualism for its own sake (and that’s not necessarily useless either).

Two important qualifications about the “other ways” of knowing outlined in this quotation: first, already knowing it in a different way doesn’t mean that this knowledge cannot be enhanced, or deepened, or advanced, by getting it clear in intellectual, or theoretical concepts. This is about interpretation and elucidation of our experiences and knowledge. I’ll come back to that.

Second: thinking that you already know what the book is talking about means that you will interpret what they’re saying through what you think you know, and thus you will not be able to get the point of the book, or at least not the whole point, because you’ve already decided that they agree with you, so you don’t need to change your position. If you don’t change your position, you don’t learn anything – except maybe that someone agrees with you; and that’s a dubious claim, since we can’t be sure whether they agreed with you, or you misunderstood them.

“It takes time to learn to attend truly to the object, to wait for meanings to emerge from a poem, rather than imposing the contents of your own head or your own gut… [A] good interpretation of a poem is firmly grounded in the poem itself, while a bad interpretation contains too much of the reader and too little of the poem.” (Belenky at al. p.98)

References

Belenky, Nancy F., Blythe M. Clinchy, Nancy R. Golderberger and Jill M. Tarule (1997[1986]) Women’s Ways of Knowing: The Development of Self, Voice and Mind, New York: Basic Books

Merleau-Ponty (1962) Phenomenology of Perception, London: Routledge.

Smith, K., 2009 ‘Meaning and Porous Being’ Thesis Eleven, 99: 7–26.

Smith, K. 2011 ‘“Deep Engagement” & Disengaged Reason’ Australian Journal of Anthropology, 22: 40–55.

Taylor, C. (1985) Philosophical Papers, Volume 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, C. (1989a) Sources of the Self. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, C. (1989b) ‘Embodied Agency’, in H. Pietersma (ed.) Merleau-Ponty: Critical Essays, pp. 1–21. Washington, DC: University Press of America.

Taylor, C. (1991) The Ethics of Authenticity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.