This week has been a fascinating writing experience for me. I’ve got a whole bunch of stuff about spiritual and emotional bypassing left over from the first week, which is still left over after the second week. The linear, rational direct part of me thinks that I should begin this week’s discussion there. But last week I was asked to focus on embodiment, which is one of my favourite subjects, so I’m going to begin there. And end there, too. So all that stuff gets held over yet again!

First, though, it was also brought to my attention that I have been throwing around the terms dualism and non-dualism without offering any explanation. So let’s begin there.

A standard philosophical definition of dualism runs as such:

The term ‘dualism’ has a variety of uses in the history of thought. In general, the idea is that, for some particular domain, there are two fundamental kinds or categories of things or principles. In theology, for example a ‘dualist’ is someone who believes that Good and Evil—or God and the Devil—are independent and more or less equal forces in the world. Dualism contrasts with monism, which is the theory that there is only one fundamental kind, category of thing or principle; and, rather less commonly, with pluralism, which is the view that there are many kinds or categories. In the philosophy of mind, dualism is the theory that the mental and the physical—or mind and body or mind and brain—are, in some sense, radically different kinds of thing. (http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/dualism/#VarDuaOnt)

When we look specifically at yoga philosophy we find a more nuanced approach (not surprisingly):

We may believe in one or the other of the philosophies of Dualism or Non-Dualism. We may see these philosophies as either contradictory or complementary.

However, when we want food or sex, or feel threatened, we automatically respond from Dualism, not Non-Dualism. If we watch a person die, or look at a corpse, are we not all struck by the mystery of apparent matter and consciousness? The higher truth quickly goes out the window in such moments and we find we are faced squarely with the Dualistic, conditioned response of the stuff of our mind.

There is something between us and Truth, the Absolute Reality, and that is called the mind. Training the mind is the starting point for Patanjali, in the Yoga Sutras. For example, one of the first things he talks about is observing which of our thoughts are useful or not useful, positive or negative. Then he directs us to learn to make choices in life on the basis of what is positive and helpful in our growth, choosing to do that which we know leads towards a stable, inner state of tranquillity. Such self-observation, self-examination, and self-training are necessary in preparation for the deeper practices.

The Dualism of the Yoga Sutra gives us detailed instructions on how to clear away the clutter so we can find the door. Non-Dualistic Vedanta philosophy gives us a sound contemplative base for deeper understanding of the nature of the door and that which is beyond. Tantra shows us how to open the door, as well as how and where to knock.

To view these as contradictory leads to confusion. To view them as complementary leads to freedom. We can apply the Dualistic and Non-Dualistic philosophies as different aspects of the same one journey within, which eventually leads to the direct experience of the center of consciousness, wherein all these questions are resolved and dissolved. (Swami Jnaneshvara Bharati http://www.swamij.com/dualism-nondualism.htm)

Note that the yin-yang symbol includes the duality within singularity – much as Swami J  is explaining. But then, unlike the theological division of good and evil, they are not independent, but interdependent – always intertwined. This is a different perspective on the differences I was discussing last week between brahma and atman, where one is a nondualistic representation of one-ness, and we might merge into the Brahmanic soup, while the other is a radical separation between human and god (i.e., dualistic).

is explaining. But then, unlike the theological division of good and evil, they are not independent, but interdependent – always intertwined. This is a different perspective on the differences I was discussing last week between brahma and atman, where one is a nondualistic representation of one-ness, and we might merge into the Brahmanic soup, while the other is a radical separation between human and god (i.e., dualistic).

This nuanced understanding of the intertwining or complementarity of the two principles will probably stand us in good stead as we begin to discuss embodiment. That is, maybe it is sometimes useful to maintain a dualistic perspective on thoughts or consciousness versus the body; but I find it highly problematic to think of the mind as radically separate or different to the body. Explaining that will be my main focus now.

Circling around to embodied experience

Having said that, let’s begin by picking up on the few of the threads of bypassing that have been left dangling. The basic concept of spiritual bypassing is that when we adopt or become attached to certain precepts of supposedly spiritual practice, we override our emotional and experiential responses in order to behave in what we perceive to be a correct fashion. The obvious example that I keep returning to is the notion of being all “love and light” and therefore repressing or denying the negative and dark thoughts that we experience. I’ve already mentioned that it’s worth thinking of this in broader terms than merely faux spirituality—all religious traditions include such precepts, but so do many philosophical, psychological and political orientations.

One participant in our discussion added the example of people who think that jealousy is an immature or irrational emotion, and therefore deny experiencing it. In a private discussion afterwards, another shared with me some thoughts about envy being treated the same way –it’s seen as base and shallow, therefore we delude ourselves into believing that we’ve risen above it; transcended that oh so petty human emotion.

I begin with these recollections to highlight a recurring tendency; our beliefs and education often get in the way of our capacity to directly access our experiences. This is a central problematic for the philosophy of the body. Our self-understandings are inseparable from our understandings of our embodiment, and our understanding of ourselves as embodied beings are strongly shaped by religious and philosophical precepts that undermine, dismiss, devalue and denigrate the facts of embodiment,

To overcome such widespread and deeply ingrained precepts, sometimes a philosopher must begin by stating the obvious. But of course, having said that’s where we must begin, I’m going to continue to prevaricate and ramble around a bit more before we get there.

Recall that last week I said the “self” into which we are inquiring has never been directly seen. It cannot be weighed, touched, measured. We only see it by inference – we deduce from figures of speech and modes of behaviour that people construct an identity, and that it is worth thinking of this identity as the self, because people refer to myself, ourselves, herself etc when we refer to someone by name – a very straightforward identifier.

Recall also that the idea of the self as a narrative is inseparable from the fact that we are embedded in social circumstances – we are social animals embedded in dialogue with others. Others call upon us to identify ourselves, to take a position, to take a stand.

All of this refers to a central problem of being human – making sense of our experience; the eternal search for meaning. Making meaning is central to what we’re talking about.

You will also recall that twice now I have provided a list of interrelated concepts: the one that included atman, brahman, self, spirit, soul, personality. All of those terms share at least one characteristic of the self – the one that I just outlined – no one has ever seen… oops; on safer turf: I have never seen any of those entities. In my experience,[*] they are all signifiers that refer to something that cannot be seen, felt, weighed, measured etc. We can say that they are all imaginary, without implying that they are unreal. If nothing else, they are really imagined, or real imaginaries.

That opens up a huge new field that would take us off topic tonight. Let me try to at least temporarily close the gaping hole by flashing back to our discussion of solipsism and the problem of other minds. A simple solipsist perspective holds that “I think”, and that’s the only thing I can be sure of. Everything else that I think I perceive may be a figment of my imagination. Perhaps you’re not really here, just a projection of my mind. If we were to accept this position, we might say that you’re all imaginary in the conventional sense, by which we mean not real.

But we are not accepting the solipsist argument, which means that you are really here. Or at least, I find that to be a satisfactory working hypothesis. From that starting point, I also accept that you have a mind, which like mine, processes your sensory experience, stores various precepts and concepts that you have acquired through your socialization and education, analyses and/or reacts to your emotional fluctuations and chatters incessantly to itself with all kinds of hopes and fears and desires and just plain ridiculousness. All of that, I imagine. I imagine that you have a mind that imagines all of those voices in your head, and imagines that I have a mind.

Our imagination is arguably the most important human faculty. What we imagine is often all too real. People live and love, fuck and fight, kill and die over things that are imagined. There is nothing more powerful than an imagination – and nothing more frightening than one running amok with unconstrained and unrefined racist bigoted xenophobic misogynistic paranoia.

That’s a lot of beating around the bush before I begin to state the obvious. But my point is that much of what we deal with is imaginary. There might be spirits. I might be a spiritual being. Maybe I have a soul. Perhaps there is a god, or many. All of the precepts that get in the way of our direct experiencing are imaginary.

But there’s one thing that I can be absolutely certain of (once I’ve rejected the solipsist argument) – I am an embodied being. I am this body. This is me. Of course there is much more to me than merely the physical object that you see before you. But there is no me that is other than or without this physical object.

I spoke about perceiving everything from this particular perspective. I cannot, for example, see the back of my head, and never will – because of the peculiar facts of my embodiment.

But a lot of what we learned about ourselves growing up either ignored, downplayed or outright problematized these facts of embodiment. We don’t even need to get into the moral stuff about touching our naughty bits or being seen by others to begin to look at this central issue. It can be seen through a simple interrogation of the language that we use to discuss ourselves.

Look: I have a foot! But who is this “I” that “has” a foot? How is this I other than this foot? I do not have a body – I am this body. This is me. If I say “my foot” or “my head” it might be a legitimate statement distinguishing mine from yours. Clearly your foot is not mine, nor is it me. But when I say “my head” as if it is something that I possess – that’s an abuse of language; it risks confusing the box-like categories of language with the cloud-like facts of life (see last week’s discussion of boxes & clouds). When it comes to our body and body parts, there are a bazillion abuses of language.

After more than 20 years, I continue to be amused every time a yoga teacher tells me “move your leg away from yourself”. Sometimes I’m reminded of that song about the detachable penis… If I had a detachable leg, I could move it away from me. But these two – no. Of course I know what she means – it’s an instruction to move it away from the torso, or the heart… Is that where the self – the “I” – is located?

That’s obviously a rhetorical question – but it’s worth noting that the ancient Chinese philosophers, the Greeks and even the Latin theologians have spent countless hours and spilled much ink trying to precisely locate the self, the spirit, the soul and how many angels can dance on the head of a pin.

Descartes

But let’s leave that and turn to a more direct consideration of the body via the mind/body dualism that plagues philosophy and medical science. It may seem like this is departing a long way from yoga philosophy, but I will try to bring it back around and tie it together again in the end.

Right now I’m going to focus on the mind/body split that is typically attributed to the 17th century French philosopher Rene Descartes. Descartes is held responsible by post-modernist and feminist philosophers for much of the misguided rationalizing of modern thinking. And rightly so. But it’s essential that we do not throw the baby out with the bathwater. If we keep that in mind, it will be easy for us to see a place for Cartesian doubt in our witnessing meditation practice – when we get around to it!

Right now I’m going to focus on the mind/body split that is typically attributed to the 17th century French philosopher Rene Descartes. Descartes is held responsible by post-modernist and feminist philosophers for much of the misguided rationalizing of modern thinking. And rightly so. But it’s essential that we do not throw the baby out with the bathwater. If we keep that in mind, it will be easy for us to see a place for Cartesian doubt in our witnessing meditation practice – when we get around to it!

The problem neither begins nor is resolved by Descartes, but his contribution is a crucial turning point. Many would argue that he lead us horribly astray – but as we saw last week, the Indian and Chinese philosophers from 500 CE were just as capable of letting reason get in the way of their empirical observations as Descartes was. In some respects, all Descartes did was elucidate on the ideas that Plato had already highlighted when he emphasized the importance of being a “man of reason”. But I get ahead of myself.

In our first discussion we touched on the issue of picking-and-choosing. While some purists think this is a degraded approach to yoga or spirituality, I suggested that with so many competing sources pointing in different directions, modern seekers of the truth have little choice but to pick-and-choose.

It has been that way for a very long time. A similar problem underpins Descartes’ development of the earliest principles of what has become the scientific method.

Descartes was faced with a similar situation to our own. Growing up in a 17th Century European society in which the collected knowledge of the ages was becoming available in books, he pondered how he was to determine which knowledge or truth claims were correct. He decided that he could not rely on anyone’s authority to adjudicate between competing claims, so he would have to test them against his experience, or against empirical evidence.

At its best, I think that’s what we do in modern yoga, too. We can read the ancient texts, we can be guided by teachers and gurus and so on – but ultimately what matters in our practice is what works for us. We are picking and choosing, we are guided by people in whom we place our faith, we follow their leads, heed their advice, etc – but ultimately, each technique, each practice, each insight must be tested against our own experience.

But I get ahead of myself again.

Descartes’ method is precisely to test each perception, each conception, each thought against … well, not his own experience. What he was seeking was some certainty about his interpretations of his experience. He set out to determine what he could be certain of, employing a technique of radical doubt. That is, he decided to doubt absolutely everything that he thought – that he thought he saw, thought he perceived, thought he felt, thought he believed – until he could strip away everything about which there was any possible doubt and uncover that of which he could be absolutely certain.

I’ve already given away the punch line to this story a couple of times. The method, although very attractive from a strictly rational perspective, leads inevitably to solipsism. It was via this method that Descartes reached that most famous maxim “I think, therefore I am” (cogito ergo sum) – because when he allowed for the possibility that the world that he perceived was potentially a delusion planted in his mind by evil daemons, or simply projections of his imagination, he stripped away any certainty that the people he engaged with, or even his own body were really certainly present. The only thing he could be absolutely certain of was that he was thinking these thoughts. The thoughts might be illusions, delusions, distortions, etc – but he was certainly thinking them.

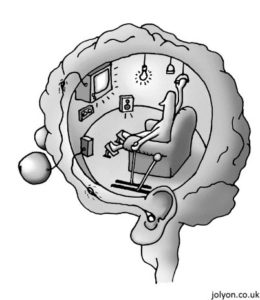

It’s only a small leap from here to the idea that “I” is located in the thought processes, in the mind, so to speak. And from there we get these ideas of a ghost in the machine or a brain in a vat – a disembodied “I”; an “I” that is independent of being embodied. This is a thinking, reasoning, plotting, processing, and cogitating “I”.

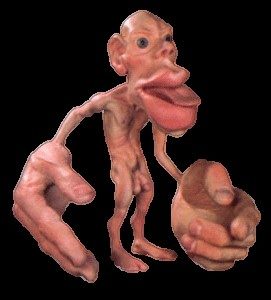

This image on the left not only refers to the idea of a ghost in the machine – it is one of the earliest conceptualisation of the Homonculus[†]—which has more recently become reduced to this idea of mapping our sensory perceptions by intensity etc [that is, this image indicates by size the most sensitive parts of the body]. The earlier conception, though, was the id

ea that there is a mini-me operating the levers of the corporeal vehicle.

Another thing that image does is highlight a recurring tendency

in thinking about the mind, and about the mind / body relationship – that is, a recurring tendency to understand this relationship in terms of the latest technology. For Descartes, the wind-up doll automaton was the newest thing – inseparable from the invention of clockwork. He literally was trying to figure out what makes us tick.

But he was also a Christian, trying to incorporate the ideas of the Holy Spirit, or soul – while developing a scientific method and at the same time avoiding the excommunication that threatened Galileo and Copernicus. So, as an important aside that we won’t pursue, Descartes is widely condemned for a dualistic reduction of being to radically separate mind and body, when in fact his conclusions reproduced the Christian trinity of Father, Son and Holy Ghost. The unfortunate legacy is that in this schema – as it is picked up by modern science, the spirit is neglected, and the Son has only secondary importance as an earthly vehicle for the Father.

Or in more direct terms, we get left with the mind/body split in which the body is incidental to the story. I mentioned earlier that part of this problem (not the problem Descartes was addressing, but the legacy of his conclusions) can be traced back much earlier – in a sense we can find it already in that phrase attributed to Plato about a “man of reason” – although some have suggested that we should refrain from pointing the finger at Plato here, and look more closely at the problems of translation from Greek into Latin and then on to us.

Plato was discussing what makes humans – anthropos – distinct from other animals. He concluded that it was our capacity for logos, translated as logic, then reason.[‡] And there’s good grounds for this, since he understood the man of reason to be superior to other men – the one who could use reason to control his passions.

We might look to the opening scene of the Iliad, where King Menelaus has said something that enrages Achilles. As Achilles reached for his sword in a hot-blooded rage, he was visited my Athena, the goddess of reason, who whispered in his ear some sage advice about not threatening the king in front of a thousand armed men. In this scene, reason prevails over the passions.

Our legacy is that reason in this story is a mental faculty, while the passions are attributed to our animal bodies / natures. From a dualistic perspective, then, reason and passion are of fundamentally different qualities.

There’s no need to dispute any of that. I am satisfied that things work out better when my passions are expressed after being reasonably or rationally processed. But over the years, and through so many moral and ethical teachings this understanding has been perverted by other dualisms of good and bad, right and wrong – it’s been misconstrued by being put into black-and-white binary boxes, rather than having to deal with cloud-like shades of grey.

This is how we get to those basic precepts that being jealous or envious is immature. Having emotional or passionate responses is human; acting them out without thinking them through might be immature. Repressing them because of overriding value judgements is bypassing.

Primacy of perception

Let’s turn now to the issue of direct experience. I mentioned the importance of the imaginary, and discussed Descartes’ doubt about the validity of his perceptions. I’ve already indicated that I reject the solipsism that Descartes’ method lead him into; but that means at some point taking a stance on what I accept to be a true and valid perception or impression.

Here I think it’s important to avoid the black-and-white of either absolute certainty or radical doubt. Sometimes, if not often, trust is required – trust in our perception, in our faculties to discern, trust in other people and so on. We touched on this briefly before, in the question of trusting our teachers. It would be a mistake to be binary about this – it’s not an either/or. I open myself to you, and try to learn what you are offering – while at the same time reserving the right to withdraw if at some point I feel that my interests are not being well looked after. This is not only about teachers – it’s how we walk down the street in a busy city full of strangers; it’s how we shop, and vote, and choose our friends and lovers. Radical doubt undermines every effort at friendship, every effort at love. But blind-unconditional trust is just stupid.

Anyway, returning to how we perceive the world – I’ve mentioned that I always approach the world from the perspective of this body. I sometimes try to imagine what the world would be like from that one, or that one; but those are things I definitely cannot know. The only thing I can know is what the world looks like and feels, smells, tastes, sounds like from right here. At the same time, while I reject Descartes’ radical doubt, I must remain aware that my perceptions are not infallible – or rather, my interpretations of what I am perceiving are fallible.

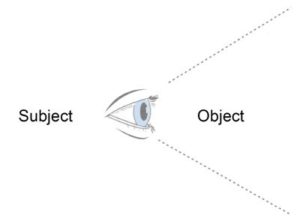

While we have spoken about the construction of the self, another way of thinking about lived experience is to discuss being a human subject. It’s not the same thing, but it’s not entirely different either. Someone [Foucault] observed that there are at least two ways of using the word subject in this sense: 1) I am subject to the world around me – whether the laws of nature, or of society; I feel the cold, and the long arm of the law; I feel your gaze, and your evaluation of me. But also, 2) I can subject the world to my will – within limits of course, but I can pick a flower, plant a garden, build a house, divert a river, burn fossil fuels and so on. In short, I am subject to, and I can subject to…

In some sense, this “being subject” is very much on the mind side of the mind/body equation. But my capacity to subject the world to my will is not only mind – I have fingers, hands, arms and legs; without them I could not subject anything to my will. The brain in the vat is completely powerless – unless it can harness some vehicle of action. As Tex Perkins put it, “My arms can be weapons or instruments of love” – my mind and my body are inseparable in the context of subjecting the world to my will. What distinguishes between weapons and instruments is our intentions – which is also at the root of our capacity to shift back and forth between being a subject and an object – which I’ll elaborate on in a moment.

In some sense, this “being subject” is very much on the mind side of the mind/body equation. But my capacity to subject the world to my will is not only mind – I have fingers, hands, arms and legs; without them I could not subject anything to my will. The brain in the vat is completely powerless – unless it can harness some vehicle of action. As Tex Perkins put it, “My arms can be weapons or instruments of love” – my mind and my body are inseparable in the context of subjecting the world to my will. What distinguishes between weapons and instruments is our intentions – which is also at the root of our capacity to shift back and forth between being a subject and an object – which I’ll elaborate on in a moment.

But first I want to stress that this difference between weapons and instruments is not reducible to intentions. Think about the idea that ran through The Matrix; in a world in which all perceived reality was in fact a computer simulation, it was possible to upload complicated knowledge like martial arts or helicopter piloting directly to the brain. In our embodied experience, though, learning such skills from a data download is impossible. Learning a martial art or how to fly a helicopter is not only a mental learning—it is an embodied learning. Every muscle, every fiber, must learn what to do. For the yogis, think about your handstands; getting into it requires training all ten fingers to grip the ground, building forearm strength to strike a balance. It requires building arm strength and shoulder flexibility as well as core strength and so much more. Not merely mental data – whatever that might mean.

But first I want to stress that this difference between weapons and instruments is not reducible to intentions. Think about the idea that ran through The Matrix; in a world in which all perceived reality was in fact a computer simulation, it was possible to upload complicated knowledge like martial arts or helicopter piloting directly to the brain. In our embodied experience, though, learning such skills from a data download is impossible. Learning a martial art or how to fly a helicopter is not only a mental learning—it is an embodied learning. Every muscle, every fiber, must learn what to do. For the yogis, think about your handstands; getting into it requires training all ten fingers to grip the ground, building forearm strength to strike a balance. It requires building arm strength and shoulder flexibility as well as core strength and so much more. Not merely mental data – whatever that might mean.

[Our discussion at this point segued into some of those yogic truisms such as “Body not stiff; Mind is stiff” as our resident yoga instructor pointed out that it is often our mind that prevents us from achieving certain poses – most specifically, in this case, the shortcomings in my handstand. No doubt she’s correct – but it would not be correct to say that this is always the case, nor is it the only limitation. Just to take one extreme example, my friend with cerebral palsy has physical limitations that will not be overcome by any amount of positive thinking. Likewise, the instructor in question acknowledges that her body as limitations that must be recognised and respected if she is to avoid injuring herself.]

This is one way in which I am “subject to” the world around me. As an embodied being I am subject to the laws of gravity, the laws of physics and bio-mechanics. My body has limitations, some of which are genetic, others are from nurture or lifestyle choices. I may or may not be genetically predisposed to run the four-minute mile – but without adequate training and nutrition I will definitely not realize any genetic potential.

Being “subject to” the world around me adds a new dimension to our discussion. I am never only a subject (except perhaps in my own mind) but am always also and simultaneously an object in the world. Unlike the self, spirit or mind, the body does have mass and extension; it can be weighed and measured. It takes up space; space that cannot be occupied by any other entity. It can be seen, heard, smelled, touched and tasted.

Long before body-image became either a political or a health issue, “I was looking back to see if you were looking back to see me looking back at you”. That is: I can be seen, and how I am seen is a matter of concern to me. This slips us back into that realm of the self, and the axes of dignity and a full life. It refers to the dialogical dimension of being in social space, of being with others and caring what others think about us.

But let’s not go back there. Instead, let’s wrap our heads around this shifting experience of being both a subject and an object, always at the same time. It means not only can I touch, but I can be touched, I can see and be seen, and so on.

One of the things that arises when we start down this path is the question of intentionality. If I can subject to, how do I do that? But also, how do I decide? How is my experience of the world shaped by my intentions towards it? This was implied when we discussed trust – if I approach the world untrustingly, my capacity to engage with it, to shape it, to subject it to my will, is radically different. But also the way I will be subject to the world is radically different depending upon how trusting I am or not.

I have written about differences between this understanding of intention and the yogic notion of intention in elephant journal and in a blog on the Svastha-yoga website. So I’m not going to repeat that here. Note that the other thing that we discussed was Castoriadis’ idea of the psychic flux, as a perpetual uprising of representation, affects and intentions. This idea is briefly outlined in the article linked above, and will be elaborated upon next week, with more on the body and intentionality.

[*] I insert these qualification in respect of the fact that others report having seen them such entities, or some of them anyway. I have my doubts, but must acknowledge that my lack of personal experience does not equate to evidence of their non-existence. The point of this qualification will become more apparent shortly, when I discuss Descartes’ method.

[†] Actually, this field is much more complicated – the earliest idea was that the homunculus was a fully formed human being already residing in the ovum, or sperm [before we knew anything about those things] which through gestation grew to be an adult human. The image I’m using here is an adaptation of an early misunderstanding in the philosophy of mind. Wikipedia will guide through these ideas if you’re interested.

[‡] As I review this, I realise that I left this dangling. Charles Taylor argues that this interpretation was a reduction, for logos includes reason, but also language with all of its vagaries – so Plato wasn’t saying a a “reasoning animal” so much as a “speaking animal”. But we’ll have to leave that discussion for another time (see Smith 2010: p.15 for details).